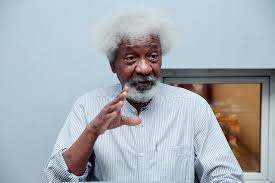

Wole Soyinka: He wrote 52 books in 64 years. Now the lion is 88, still writing

Wole Soyinka: He wrote 52 books in 64 years. Now the lion is 88, still writing

By Ernest Ogunyemi

The Nigerian writer and activist Wole Soyinka turned 87 this week. He was born on July 13, 1934, in Aké, Abeokuta, a town in southwestern Nigeria.

One of the greatest writers of his generation, Soyinka produced plays, novels, poems, and essays that explore African art and worldviews and serve as witnesses to sociopolitical issues in the world. The multi-talented artist, wrote the poet and academic Tanure Ojaide in Black American Literature Forum, “combines traditional African and Western influences so dexterously that he creates a personal authenticity.”

In 1975, Soyinka edited Poems of Black Africa, considered by many scholars to be the first anthology of poems that truly captures the abundant identities and realities of Black Africa. From 1975 to 1979, he was a Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Ife, now Obafemi Awolowo University. He has since taught at Harvard, Oxford, and Yale.

In 1986, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first African and Black writer to be so honoured. In December 2017, he received the Europe Theater Prize’s “Special Prize.”

In his introduction to the Africa39 anthology, he wrote: “The primary function of literature is to capture and expand reality. It is futile therefore to attempt to circumscribe African creative territory, least of all by conformism to any literary ideology that then aspires to be the tail that wags the dog. It projects its enhanced vision of Life’s potential, its possibilities, narrates its triumphs and failures. Its offerings include empowerment of the oppressed and the subjugation of power. It will not attempt to do all of this at once—that will only clot up the very passages of its own proceeding.”

To celebrate Soyinka’s 87th birthday, here is a guide to his full-length published works, categorized by genre. It comprises 25 plays, 10 essay collections, seven poetry collections, five memoirs, three novels, and two translated works. (Publishers’ synopses appear in quotes.)

Plays

The Invention (1957)

Widely regarded as Soyinka’s first play, first staged at London’s Royal Court Theatre in 1959, The Invention “reflects the obsession with race that marked the apartheid regime, and prophetically depicts the crumbling of the apartheid system in the futuristic setting of Johannesburg in 1976.”

The Swamp Dwellers (1958)

This play is a close study of the conflict between the old way of living and the new in colonial Africa. Through “the swamp dwellers,” Soyinka explored power, social injustice, hypocrisy, and tyranny.

A Quality of Violence (1959)

The Lion and the Jewel (1959)

Set in Ilujinle, a Yoruba village, this rich play chronicles how Baraka, the village’s viceroyal chieftain, fights with Lakunle, a semi-literate Westernised teacher, over the right to marry Sidi, the village belle. Baraka and Sidi are the titular “lion” and “jewel.” It is one of Soyinka’s best-known plays.

The Trials of Brother Jero (1960)

Produced for the first time at Mellanby Hall, University College, Ibadan, this is a light satiric comedy in which Soyinka has a go at religious hypocrisy. The titular Brother Jero is a rogue, and he masterfully manipulates his followers who are hungry for money, power, and a rise in social status.

A Dance of the Forests (1960)

It was first presented at the Nigerian Independence celebrations. Staged by the playwright’s drama group The Masks, the play satirizes “the fledgling nation by stripping it of romantic legend and by showing that the present is no more a golden age than was the past.”

My Father’s Burden (1960)

A television drama, this is the story of Nwane (the father), whose sin is being visited upon Onya (the son). Onya, a young government official, gives up all privileges to correct the accursed inheritance he bears. In it, Soyinka presents a way of purging corruption from the government.

The Strong Breed (1964)

A highly symbolic play, it tells the story of Eman, who has to lay down his life to save the village. Soyinka engages death and rituals and several superstitious beliefs that abound in the Yoruba religion and worldview.

Before the Blackout (1964)

This play highlights the satiric thrust of Soyinka with thirteen sketches of various facets of the Nigerian condition.

Kongi’s Harvest (1964)

Premiered at the first Negro Arts Festival in Darkar, in April 1966, the play is the story of President Kongi, the dictator of an African country, who is trying to modernize and unify the nation by all means possible, after deposing King Oba Danlola. It was adapted as a film by Ossie Davies in 1970.

The Detainee (1965)

A radio play, the plot foreshadows the writer’s own imprisonment and his now familiar concerns about the vagaries of African politics.

The Road (1965)

A tragicomedy about a day in the strange life of a group of drivers and their associates, all of whom are uneducated except for Professor, who, among other things, forges licenses. Set in a poor neighborhood in a Nigerian city that is rapidly changing, it engages unemployment, modernism, and the spiritual.

SUGGESTED READING:

The Booker Prize 2021 Longlist

The Bacchae of Euripides: A Communion Rite (1973)

An adaptation of the Athenian playwright Euripides’ The Bacchae, Soyinka infuses this with Yoruba thought and a chorus; and in its climatic head, unlike in Euripides’ where Thebes dissolves into chaos, blood gushes from Pentheus’s head, which the people drink. By drinking, the people partake in power, which fulfils the play’s subtitle: “A Communion Rite.”

Camwood on the Leaves (1973)

The profound story of two families in a small town and a series of incidents that results in their conflict. Here, Soyinka engages identity and its politics, and politics and its identity.

Jero’s Metamorphosis (1973)

The beach where Brother Jero manipulated his devotees has now been populated by several other “prophets,” and by some cunning he has accessed a confidential file that shows plans to turn the beach into a prosecution ground. At the end of this light satiric comedy, Brother Jero wins.

Death and the King’s Horseman (1975)

Based on events that took place in Oyo, a Yoruba city in Nigeria, in 1946, Soyinka’s powerful play is about the intertwined lives of Elesin Oba, the king’s chief horseman; his son, Olunde, studying medicine in England; and Simon Pilkings, the colonial district officer. The king has died and Elesin is expected by law and custom to die by suicide and accompany his ruler to heaven. The stage is set for a dramatic climax when Pilkings learns of the ritual and decides to intervene and Elesin’s son arrives home.

Opera Wonyosi (1977)

A retelling of John Gay’s The Beggars Opera and Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, here, Soyinka employs dark humour to make vital comments on Nigeria’s social and political situation.

Requiem for a Futurologist (1983)

With a hero like Jero, Soyinka scathingly presents, once again, the rapidly deteriorating situation of the average Nigerian and the chaos, “penkelemes” or “painful mess,” that rules.

A Play of Giants (1984)

Set in the “Bugaran” Embassy in New York, the play depicts several of Africa’s most ridiculous tyrants. A sculptor is immortalizing them, but they are hard to set in stone—one, because of their constant concern about their countries collapsing (or leadership falling into other hands), especially in their absence.

Childe Internationale (1987)

A single scene of 26 pages, the characters are: the politician, his wife, their daughter Titi, and her American boyfriend Alvin. The conflict between the African culture and practices and the Western ways is presented through the Politician who feels disrespected at the behaviour of his wife and daughter who have just arrived from Britain.

From Zia with Love and A Scourge of Hyacinths (1992)

When the military decrees that a crime carrying a prison sentence now retroactively warrants summary execution, confusion and fear permeate a society where the brutality and injustice of military rule is parodied by life inside prison. Both plays are based on a singular real event that took place in Nigeria during Buhari’s regime in 1984.

The Beatification of Area Boy (1996)

Set in Nigeria, amid scenes of everyday racketeering and general disquiet, the police try to clear the area of undesirables, as a traditional wedding between two illustrious and ambitious families is about to take place.

Document of Identity (1999)

Partly autobiographical, this play is set during the General Sani Abacha regime, and it shows the predicament of political asylum seekers in London.

King Baabu (2001)

A naked satire on the regime of General Abacha in Nigeria, the play chronicles the debauched rule of General Basha Bash, who takes power in a coup and exchanges his general’s uniform for a robe and crown re-christening himself King Baabu. In the manner of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi, Soyinka develops a special childish language for his cast of characters, who have names like Potipoo and General Uzi. It weaves together burlesque comedy, theatrical excess, and storytelling.

Alápatà Àpáta: A Play for Yorubafonia, Class for Xenophiles (2011)

In this play, Soyinka makes a mockery of politics and power play in Nigeria, using the circumstances surrounding the newfound, idle lifestyle of a newly-retired butcher, Alaba.

Novels

The Interpreters (1966)

Drawn together by their hopes, loves, dissatisfactions, and the daily lives and deaths around them, five young Nigerian intellectuals evoke a new lost and found generation. From their wild drinking bouts at the Club Cambana to their individual pursuits of personal and professional integrity, they simultaneously find themselves as seekers and prophets as they attempt to define their identity in a world where their cultural past and Western-influenced present are brought into conflict. This novel combines the uniquely sensitive observations of Soyinka with his trademark mad comedy.

Season of Anomy (1972)

In an unnamed country in Africa, Ofeyi writes propaganda jingles for the National Cocoa Corporation. As a part of his job, he is sent to Aiyeru, a small coastal village whose geographic landscape has largely kept the village insulated from the government and its corruption, to promote the company. Here, Ofeyi witnesses a traditional way of life and values that run counter to their country; this creates an inner shift. In a challenge against the government, Ofeyi soon finds that the revolution may be too difficult to control.

Chronicles of the Happiest People on Earth (forthcoming, Bookcraft, 2021)

Soyinka aims directly at the corridors of power as he warns against corruption both of high office and of the soul, with a dazzling lightness of touch and gleeful irreverence. This novel is at once a savagely witty whodunit, a scathing indictment of Nigeria’s political elite, and a provocative call to arms from one of the country’s most relentless political activists and an international literary giant.

Poetry Collections

Idanre and Other Poems (1973)

This collection consists of a long poem and a number of shorter ones. “Idanre,” the long one, was written especially for the Commonwealth (British) Arts Festival in 1965 and is a creation myth of Ogun, the Yoruba God of Iron. The other poems range from a meditation on the news of the October Massacres in Northern Nigeria (1966) to a wry lament “To My First White Hairs” and the love poem “Psalm.”

A Big Airplane Crashed into The Earth, originally titled Poems from Prison (1969)

SUGGESTED READING:

Bookshop.org Announces Shortlist for New Futures Programme

A Shuttle in the Crypt (1971)

A collection of poems about human encounters and inhuman isolation, based on Soyinka’s reflections on his imprisonment in Nigeria.

Ogun Abibiman (1976)

A call to Black people to join in fighting for liberation in South Africa, centering Ogun, the Yoruba deity known for his fierceness and unfaltering delivery of justice.

Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems (1988)

The Nigerian Nobel laureate presents a collection of new poems in homage to South African leader Nelson Mandela, excoriating political corruption and moral flabbiness and meditating on the ambivalences and ambiguities of life and love.

Early Poems (1997)

A collection of both Idanre and Other Poems and A Shuttle in the Crypt.

Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known (2002)

Satirical and lyrical, his fourth collection spans his experience of exile from Nigeria as well as the journeys that followed his Nobel Prize for Literature. There are reflections on the deaths of politicians, dictators, and dissident friends as well as invocations to fellow writers Ken Saro-Wiwa, Josef Brodsky, and Chinua Achebe, among them.

Essays

Myth, Literature and the African World (1976)

Here, Soyinka analyses the interconnecting worlds of myth, ritual, and literature in Africa. The ways in which the African world perceives itself as a cultural entity, and the differences between its essential unity of experience and literary form and the sense of division pervading Western literature, are just some of the issues addressed. The centrality of ritual gives drama a prominent place in his discussion, but Soyinka deals in equally illuminating ways with contemporary poetry and fiction. Above all, the fascinating insights in this book serve to highlight the importance of African criticism in addition to the literary and cultural achievements which are the subject of its penetrating analysis.

Art, Dialogue, and Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture (1988)

A fierce and provocative contribution to the debate on multi-culturalism, this book brings together 19 iconoclastic essays from the previous 25 years on African, European, and American literature, culture, and politics—many of which are published here for the first time. It gives a startling vision of culture in our times.

The Black Man and the Veil: Beyond the Berlin Wall (1990)

The Credo of Being and Nothingness (1991)

The first in the series of Olufosoye Annual Lectures on Religions, delivered at the University of Ibadan in 1991, here, in his characteristically stimulating way, Soyinka discusses the religions of Nigeria in their national context, and other religions from around the world.

The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis (1996)

In this book, Soyinka, whose own Nigerian passport was confiscated by General Abacha in 1994, explores the history and future of Nigeria in a compelling jeremiad that is as intense as it is provocative, learned, and wide-ranging. He deftly explains the shifting dramatis personae of Nigerian history and politics to westerners unfamiliar with the players and the process, tracing the growth of Nigeria as a player in the world economy, through the corrupt regime of Babangida, the civil war occasioned by the secession of Biafra under the leadership of Chief Odumegwu Ojukwu, the lameduck reign of Ernest Shonekan, and the coup led by General Sani Abacha. Wole Soyinka argues that “a glance at the mildewed tapestry of the stubbornly unfinished nation edifice is necessary” to explain where Nigeria can go next.

The Burden of Memory, the Muse of Forgiveness (2000)

Wole Soyinka considers all of Africa, and all the world, as he poses this question: Once repression stops, is reconciliation between oppressor and victim possible? In the face of centuries-long devastation wrought on the African continent and her Diaspora by slavery, colonialism, Apartheid, and the manifold faces of racism, what form of recompense could possibly suffice? In a voice as eloquent and humane as it is forceful, Soyinka boldly challenges in these pages the notions of simple forgiveness, confession, and absolution as strategies for social healing. He turns to art, the generous vessel that can hold together the burden of memory and the hope of forgiveness.

Climate of Fear: The Quest for Dignity in a Dehumanized World (2004)

In Soyinka’s BBC Reith Lectures, he suggests that the climate of fear that enveloped the world, following September 11, 2001, was sparked long before the attack. It can be traced instead to 1989, when a passenger plane was brought down by terrorists over the Republic of Niger. From Niger to lower Manhattan to Madrid, he chronicles how this invisible threat has erased distinctions between citizens and soldiers, and how it is aimed at all of us. He explores the conflict between power and freedom, the motives behind unthinkable acts of violence, and the meaning of human dignity.

New Imperialism (2009)

This book contains Soyinka’s lecture as the Distinguished Nyerere Lecturer in 2009. He explores the multifaceted concepts and practices of imperialism and relates these to past and present human experiences across the world, including Africa.

Of Africa (2012)

Soyinka offers a wide-ranging inquiry into Africa’s culture, religion, history, imagination, and identity. He seeks to understand how the continent’s history is entwined with the histories of others, while exploring Africa’s truest assets. His exploration of Africa relocates the continent in the reader’s imagination and maps a course toward an African future of peace and affirmation.

Beyond Aesthetics: Use, Abuse, and Dissonance in African Art Traditions (2019)

His most recent collection of essays is an intimate reflection on culture and tradition, creativity and power, which draws on Soyinka’s lifetime commitment to aesthetic encounter.

Memoirs

The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972)

SUGGESTED READING:

After 5 Years, Afreada Goes to Print

Here is a record of the 27 months during which Soyinka was held as a political prisoner, from 1967 to 1969, during the Biafran War.

Aké: The Years of Childhood (1981)

A dazzling memoir, Aké gives us the story of Soyinka’s boyhood before and during World War II in a Yoruba village called Aké. A relentlessly curious child who loved books and getting into trouble, Soyinka grew up on a parsonage compound, raised by Christian parents and by a grandfather who introduced him to Yoruba spiritual traditions. His vivid evocation of the colorful sights, sounds, and aromas of the world that shaped him is both lyrically beautiful and laced with humor and the sheer delight of a child’s-eye view. A classic of African autobiography, Aké is a transcendently timeless portrait of the mysteries of childhood.

It was named one of “Africa’s 100 Best Books of the Twentieth Century.”

Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years: A Memoir 1945–1965 (1989)

A sequel to Aké, this book tells the story of Maren, Soyinka’s alter ego, as he moves from school days in Ibadan to student days in Leeds, stints as a play reader in London, an abortive attempt to become a cafe singer in Paris, travels to other parts of the world, and finally a post as research fellow in drama back in Ibadan. Throughout all his travels he becomes increasingly antagonistic to the corrupt authorities, opposing them firstly through writing and then by direct action.

Isara: A Voyage Around Essay (1990)

In this semifictional account, Soyinka examines the colonial period in his native Nigeria during his father’s and grandfather’s generations, revealing the human complexities of politicall oppression.

You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006)

A chronicle of his turbulent life as an adult in (and in exile from) his beloved, beleaguered homeland. In the tough, humane, and lyrical language that has typified his plays and novels, Soyinka captures the indomitable spirit of Nigeria itself by bringing to life the friends and family who bolstered and inspired him, and by describing the pioneering theater works that defied censure and tradition.

Translated Work

The Forest of a Thousand Demons: A Hunter’s Saga, a translation of D. O. Fagunwa’s Ògbójú Ọdẹ nínú Igbó Irúnmalẹ̀ (1968)

A translation into English of the first full-length novel in Yoruba, and one of the first to be written in an African language, this book is triumph of the mythic imagination. The narrative unfolds in a landscape where, true to Yoruba cosmology, human, natural, and supernatural beings are compellingly and wonderfully alive at once.

In the Forest of Olodumare: A Translation of D.O. Fagunwa’s Igbo Olodumare (2010)

A direct translation, this is a dialectical expose of the creative ingenuity, inspiration, and use of language that characterize both Soyinka and Fagunwa’s work.