JUDICIAL TERRORISM IN NIGERIA

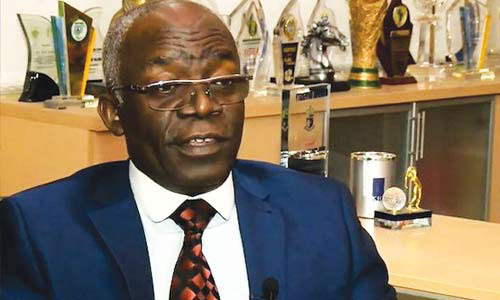

By Femi Falana SAN

A short reflection on ethnic and judicial persecution in Nigeria

On May 19, 1992, Dr. Beko Ransome-kuti, Baba Omolola and I were captured in Lagos and dumped in Kuje Prison where we were detained under the obnoxious State Security (Detention of Persons) Decree No 2 of 1984. A week later, Chief Gani Fawehinmi SAN was arrested and brought to Kuje Prison to join us. Fawehinmi’s ‘offence’ was that he had the temerity to file three fundamental rights cases which had challenged the validity of our arrest and detention.

It was while we were in Kuje prison that we met General Zamani Lekwot (rtd). He was held vicariously liable for the unfortunate bloody dispute between the Zango Kataf and the Fulani communities in Southern Kaduna. We have since them maintained a close relationship which led to my choice as the reviewer of this book.

This is a riveting book on the macabre trial and death sentences passed on Major-General Zamani Lekwot and five other Kataf indigenes over the 1992 Zangon Kataf crisis and their ridiculous trial which was marred with obvious Judicial abuse by the tribunal. Chairman of the tribunal, Justice Benedict Okadigbo incessantly delved into the arena during the trial, exhibiting patent and unabashed bias. The book encapsulates details of this judicial perfidy. It was like a scene from Stephen Tumim’s epic book – “Great legal disasters”.

In this 114-page book with seven chapters, the author deftly navigates the judicial intrigues and perfidy of the Civil Disturbances judicial tribunal, headed by Justice Benedict Okadigbo.

In the Foreword to the book by Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah, the cleric said inter alia: “Sadly but truly, with military tribunals, judgments were often concluded before the Tribunal itself was constituted. Its job was often simply to present a semblance of process. Their duty was either to twist, turn or manufacture evidence to achieve this end. These tribunals would go down as the greatest acts of malfeasance against justice in our society”.

The seven-chapter book started with an introduction to the crisis, particularly a letter dated February 3, 1940, written by the Emir of Zazzau, Ja’afaru, to one Dallatu Mohammed, which was originally written in Hausa, and which seemed to have set the stage for internecine ethnic conglict of attrition between the people referred to in the letter as “infidels” and the other settlers -effectively between the predominantly Christian Katafs and the Muslims. The 1940 letter was reproduced in this book.

Chapter one of the book dealt with the initial charges against General Lekwot and five others, who were leaders in Zangon Kataf. The charges against them before the Civil disturbances (Special tribunal), were that of unlawful assembly. However, after the prosecution witnesses had given evidences and defence had started giving their evidences and the government realizing that the evidences of the defence could lead to their acquittal, the government dramatically filed a nolle prosequi, discontinued the trial and substituted it with new charges of culpable homicide punishable with death and that was the beginning of the macabre drama. The author came out with all the full text of the charges and the key rulings. Even when the defendants approached the court of appeal in one of the rulings, the tribunal treated the appellate court with contempt and proceeded with the trial.

From that stage, when the trial started, things took to a dizzying dimension, as the tribunal chairman, Justice Benedict Okadigbo did not put anyone in doubt about his partiality as he regularly had altercations with the defence team led by the inimitable Chief G.O. K. Ajayi,SAN to the extent that Chief Ajayi, an otherwise urbane gentleman, had to engage in heated altercation with the tribunal chairman, a situation that made the defence counsel to withdraw their appearance from the tribunal when it was obvious that the tribunal had made up its mind to guillotine General Lekwot and his five co-defendants.

It reminds me of how the Late Chief Gani Fawehinmi and my humble self withdrew from the Ogoni tribunal in 1995 when it was quite obvious that the tribunal had made up its mind to condemn Ken Saro Wiwa and his co-defendants to death.

This book detailed how the tribunal hurriedly adjourned after the withdrawal of the defence counsel , for judgment, even when the prosecution had not finished calling its witnesses and defence had not even opened evidence.

It was therefore not a surprise that the tribunal condemned all the six defendants to death by hanging and they were immediately moved to the condemned cells.

The book detailed how the national and international Human Rights bodies rose to the occasion to condemn the judicial perfidy. One of the bodies in Nigeria, Constitutional Rights project(CRP), apart from lodging a petition at the African Commission of Human and people’s Rights in Banjul, similarly filed an application at the Lagos High court to stop the planned execution. The matter was heard by Justice Morounkeji Onalaja (later JCA) of blessed memory, who gave an order stopping the planned execution. He also ruled that by virtue of the African Charter on Human and people’s rights, he had the jurisdiction to adjudicate on the matter and that CRP had the locus standi to bring the action. The full ruling is contained in the book.

And that stopped the Babangida junta from executing them. By way of extrapolation, a similar move was made by the CRP in 1995 to stop the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa when Ken Saro-Wiwa and others were condemned to death and the then Chief Judge of the Federal High court, Justice Babatunde Belgore refused to assign the case till they were executed.

The author also detailed in chapter six, series of newspaper editorials deprecating the macabre trial, while chapter seven, the last chapter, contained the decision of the African Commission of Human and people’s rights, nullifying the trial.

This is a well-researched resource book that would enrich our discourse of judicial integrity and perfidy. It came at the right time when there is public perception of our judex being asphyxiated by political influences, a worrisome phenomenon that needs be urgently addressed.

I want to join Bishop Matthew Kukah in congratulating the author for documenting this judicial perfidy for posterity.

As Bishop Kukah said:”By laying bare the facts and letting them speak for themselves, Mr Akinnola has rendered a service not to the people of Zangon Kataf, but to all those who are serious about the prospects of our living together in peace and harmony as common citizens with equal rights before the law in the same country. The struggle for justice is often a lonely one, but Richard has done great service by laying bare the facts of this saga. This book is a bouquet of love, a vade mecum for all those who struggle for justice and peace.”